The Three Mile Island Nuclear Accident

by: The Calamity Calendar Team

March 28, 1979

4:00 AM: An Ordinary Morning in Pennsylvania

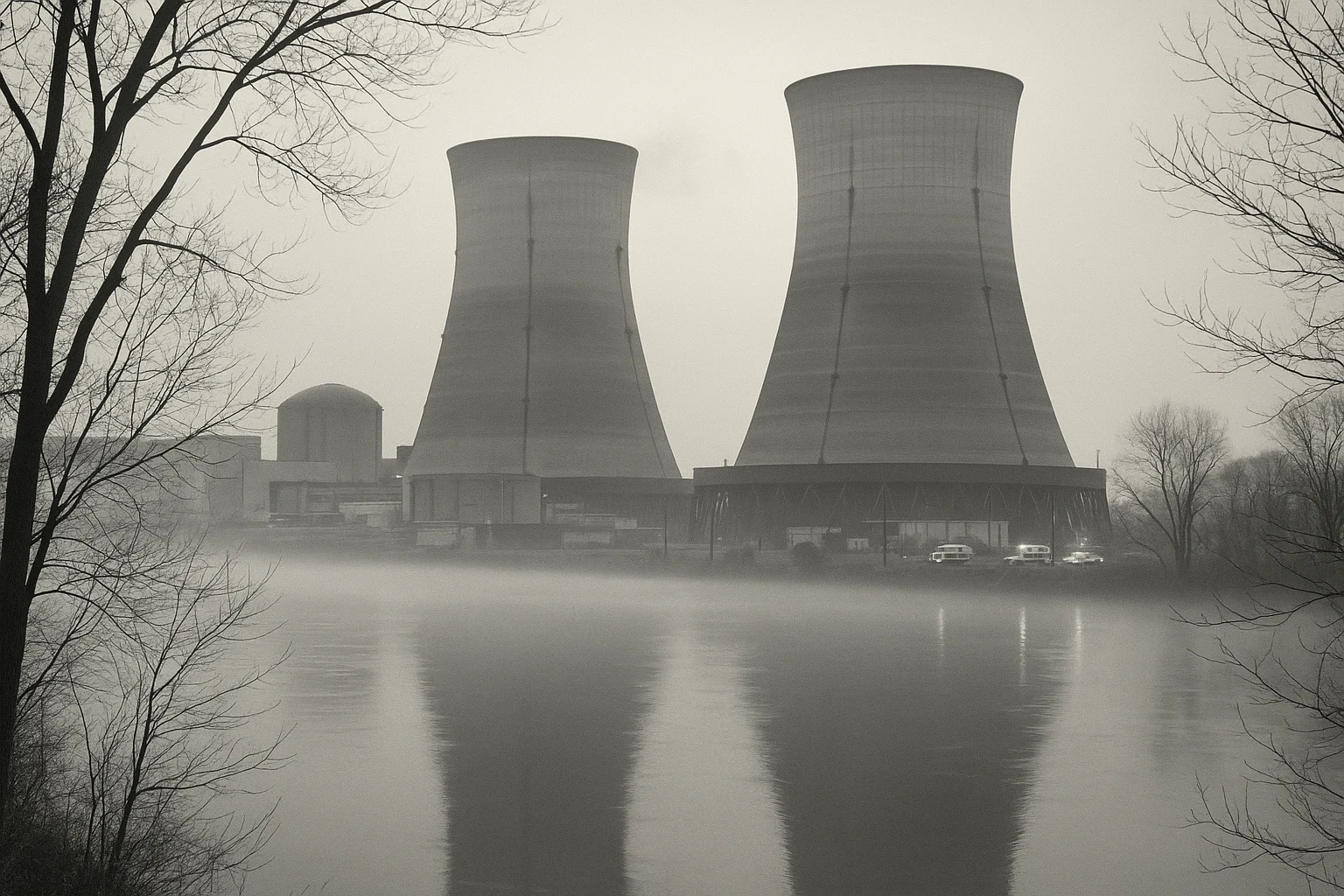

On most days, the island was just another part of the Susquehanna River—a misplaced chunk of land whose only claim to fame was the latticework of metal, the concrete domes, and the two enormous cooling towers that loomed against the southeastern Pennsylvania sky. It was a place busy with quietly humming machinery and the vigilance of night-shift operators, its curves and pipes outlined in the odd, bluish light that only certain kinds of work know.

But on March 28, 1979, at 4:00 in the morning, Three Mile Island became something else entirely. What began as a routine early shift—the kind where black coffee and dull alarms mingle in equal parts—suddenly transformed into what would become the most serious accident in U.S. commercial nuclear history.

Power, Promises, and Precedents

By the late 1970s, nuclear energy was woven deep into the American imagination. The promise: energy too cheap to meter, clean and almost infinite. The reality: a growing webwork of reactors, each insulated by assurances that regulation and engineering could outsmart even the most unpredictable risks.

Three Mile Island was meant to be proof of this—state-of-the-art, with failsafes for every foreseeable disaster. Its twin reactors, TMI-1 and TMI-2, represented some of the most advanced nuclear technology then in service. TMI-2, the newer unit, had fired up operations just three months prior to the events of that March morning. Operators were drilled in procedures, and backup systems were double-checked by inspectors. Few doubted the wisdom—and safety—of it all.

Except, of course, for the handful of critics remembering Browns Ferry in 1975, where a fire in a cable tray revealed just how easily things could unravel. For them, any calm was only temporary.

A Simple Malfunction, or Something More?

The tipping point came in a whisper: a pump failure linked to what amounted to simple maintenance. The main feedwater pumps at Unit 2, responsible for shifting cooling water to the steam generators, came to a halt. The reactor registered the loss and did as it was designed to do—it SCRAMMED, performing an automatic emergency shutdown.

Thanks for subscribing!

But then, the first hint of deeper trouble: a relief valve, designed to release moments of excess pressure, stuck open after the initial jolt. A red light on the control panel blinked the all-clear, misleading the operators; the machinery lied by omission. Coolant already boiling and roiling inside the reactor core kept flowing—and kept leaking, minute by minute, through the valve.

It’s easy, with hindsight, to wonder how anyone could miss this. The control room’s display of dials, blinking lights, and meters was meant to make sense of chaos, yet on that morning, it only fueled it. The room filled with tension as pressure readings, water levels, and alarms refused to tell the same story. Was the core too full—or starving? No one was entirely sure, and the relief valve continued its silent sabotage.

Human Error: A Bleak Domino

The crew, feeling pressure to avoid flooding the reactor pressure vessel (a scenario their training had drilled in as dangerous), misread the cues. They dialed back the emergency core cooling. But the real danger was the opposite—less water, not more. In the dark hours between four and eight, the nuclear fuel rods, clad in zirconium, began to peek above the shrinking pool of coolant, growing hotter, then dangerously so.

Long after the fact, investigators would trace the string of misinterpretations and catch it: the system wasn’t broken by a single moment of oversight but by a slow-motion sequence of misunderstandings, all entirely human.

Inside the containment building, heat kept rising. Hydrogen—formed from a high-temperature chemical reaction—began to gather in a bubble. The possibility of not just a meltdown but an impending explosion was luminous, tense, and, for those inside, largely invisible.

Dawn: A Community Unaware

The sun came up over the Susquehanna River, painting the towers and their thin sheaths of cloud in golden light. Outside the plant, no alarms sounded. In Harrisburg and the nearby towns, families prepared for work and school, unaware that inside those bleach-white domes, the worst American nuclear event so far was unfolding.

It would be hours before the outside world caught a whiff of the crisis. Operators struggled with conflicting signals and mounting reactor temperatures. Attempts to cool the core lagged behind the need. It wasn’t until radiation monitors signaled higher readings—and someone finally called the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission—that the slow-motion disaster began to break the surface for the public.

The News Breaks, But Clarity Doesn’t

Official word trickled out with an almost purposeful inertia. At first, NRC briefings to the press played down the risk—a “minor incident,” they said, “no serious threat to health.” Inside the plant, many knew otherwise.

By midday, with radiation confirmed outside the reactor and engineers struggling to calculate the implications of the hydrogen bubble now forming inside the beast, the messaging shifted. Pennsylvania’s governor, Dick Thornburgh, told the public that pregnant women and preschool-aged children within five miles should leave—just a precaution, officials insisted. Yet, the word was already out: the worst-case scenario was being quietly considered.

On the highways outside Harrisburg, cars began to line up as families, shaken by rumor and the sharp tang of fear, packed what they could and drove. Radio chatter mixed official pronouncements with the worries of neighbors—how far was five miles, anyway, and what did ‘precaution’ really mean?

Watching the Bubble

Throughout March 29th and 30th, control room drama mingled with street-level anxiety. Public officials worried aloud about the hydrogen bubble, even as some technical staff already suspected the worst had likely passed; the explosion risk, later analysis would reveal, had been overestimated in real time. But at the time, it hung over the scene like a distant thunderstorm—impossible to ignore.

On March 30th, the operators finally managed to shepherd the plant into “cold shutdown.” Temperatures in the reactor dropped, the bubble dissipated. No one witnessed a dramatic ending or cinematic release of fury. The real terror, it turned out, wasn’t an explosion but absence—of clear answers, of confidence, of trust in the system.

Counting the Costs

Cleanup took fourteen years and untold dollars: over $1 billion by the time the final tally was made. The physical damage was obvious—the fuel core inside TMI-2 partially melted, warped by temperatures it was never meant to endure. More than 100 tons of uranium fuel had to be hauled away, along with millions of gallons of radioactive water, each step more complicated by paperwork, technical hurdles, and public scrutiny.

But what of the human costs? Unlike Chernobyl or Fukushima, there were no bodies in the streets, no clear wave of sickness or visible scars etched onto the county. Epidemiological studies time and again found no spike in cancers, no surge in birth defects. The radiation that did escape increased local exposure by a fraction—measured in millirems, less than what many would get from an extra chest X-ray.

Of course, pain often doesn’t need numbers or autopsies. For thousands who lived nearby, the dread lingered for years. Some left and never returned, others avoided the river altogether, just in case. Lawsuits and claims came and went. For the operators—some of whom grew physically ill from the weight of what had almost happened—the aftershocks were personal and unending.

Fallout Beyond Physics

When a reactor staggers, it does not just damage steel and uranium. For the American nuclear industry, Three Mile Island was a breach of confidence. Dozens of planned nuclear stations were canceled. Whole books were rewritten, not just of safety codes but of public opinion. Funding dried up; politicians distanced themselves; environmental groups rallied.

Inside government, the President’s Commission—known as the Kemeny Commission—dug into the root causes. Their October 1979 report was unsparing: “There were a series of human, institutional, and regulatory failures that led to the accident.” They recommended stronger training, improved instrument panels, clearer lines of authority, and better public information.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission took those recommendations seriously. Emergency planning transformed—now, evacuation routes had to be mapped and public warning systems tested. Operator training became relentless, and the entire industry, under a newly created Institute of Nuclear Power Operations, was prodded into regular, often uncomfortable, self-examination.

The Island Now

Today, Three Mile Island is quieter than most would expect. In 2019, its remaining reactor, TMI-1, powered down for the last time. The twin domes stand silent over the river, the machinery within checked more often by geese than by engineers. TMI-2 itself remains in place, monitored, mantled in regulations, and bearing the memory of what almost happened—a partial meltdown that, by a thin margin, did not become disaster.

If you stop by the shoreline, the water still laps the island just as it did before dawn that March. Most days, there’s nothing to suggest how tense things were. The sense of danger has faded, but the lessons haven’t. In textbooks and documentaries, in the nervous jokes of engineers, in the hard-won patience of every plant operator since, the story of Three Mile Island endures—not just as a caution, but as a reminder of what can happen when systems are trusted more than people, and how, in the end, it is people who must sort out the mess when things go wrong.

What Remains

The Three Mile Island accident didn’t kill anyone, but it shook a nation’s faith—in technology, in expertise, in the men and women behind the glass. Today, long-term health studies remain consistent: the incident’s radiation was negligible outside the plant walls. But the shadow it cast was psychological, social, and political.

Every debate about energy—about what we’re willing to risk, and how much trust we are willing to lend—still passes through that tiny sliver of land in the Susquehanna. Three Mile Island is a name written not just in the histories of power and policy, but in the anxious murmurs of emergency drills, in the half-remembered news broadcasts of 1979, and in the lessons learned—sometimes the hard way—about the limits of human certainty.

It began in the still, early morning with a stuck valve and confusion. It ends, for now, with a vigilant silence, the cooling towers watching over the river. And the story persists—undramatic, but vital: a warning not of what was lost, but of what was almost lost, and of how easy it is, even with the best technology, to lose control.

Stay in the Loop!

Become a Calamity Insider and get exclusive Calamity Calendar updates delivered straight to your inbox.

Thanks! You're now subscribed.